The Skálholt Map: the Norse Exploration of America, and the Politics of Discovery

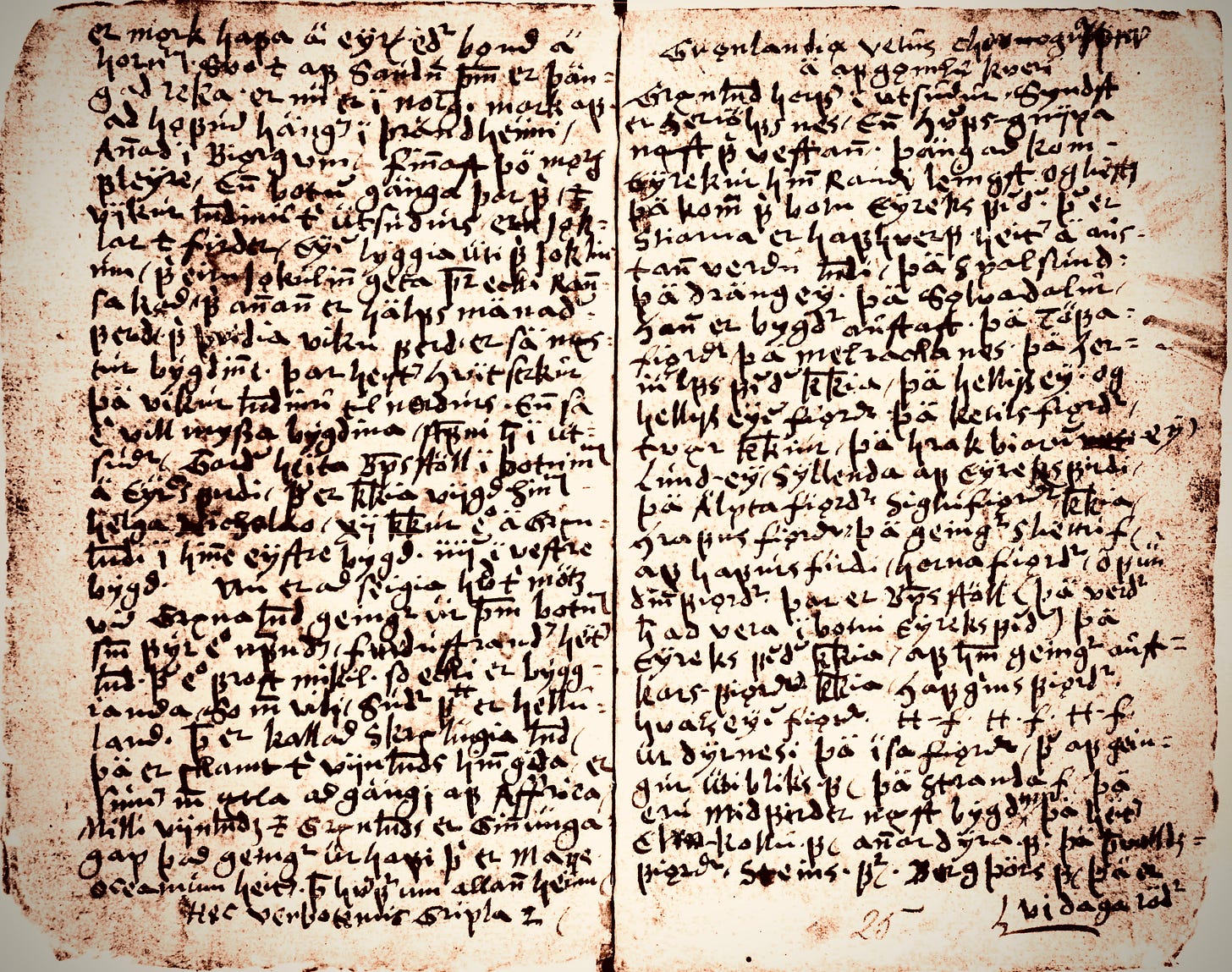

In the heart of southern Iceland lies what was once one of the island’s most important religious and cultural centers: Skálholt. For over seven centuries it served as a bishopric and was home to Iceland’s first official school, founded in 1056. But Skálholt is also known for a cartographic artifact as fascinating as it is mysterious: the Skálholt Map (Skálholtskortið), created around 1590 by the scholar Sigurður Stefánsson, then rector of the cathedral school (in the 17th-century copy shown below, he is referred to as “Sigurdus Stephanius islandicus, vir eruditus”).

Today little known outside academic circles, the Skálholt Map is notable for being considered authentic—unlike the more famous Vinland Map held at Yale—and, in many ways, visionary. Its purpose? To chart on a map of the North Atlantic the American lands described in the Vinland Sagas (The Saga of Eiríkur the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders), 13th-century narratives recounting Norse exploration of North America around the year 1000.

A blend of fact and fable

The map survives in a 1669 copy made by Bishop Þórður (Thorlacius) Þorláksson (1637–1697), as part of a Danish-Latin treatise on Greenland. The text draws on a geographical description of the region by Björn Jónsson of Skarðsá (1574–1655)—a prominent steward, legal assemblyman, and chronicler—who compiled the so-called Greenland Annals, which are actually a collection of various writings about Greenland, preserved in the manuscript AM 115 8vo.

The map Þórður copied is a mesmerizing mosaic of real, imagined, and legendary places. To the southeast lie Ireland, Britain, the Orkneys, Shetland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and the elusive Frisland—a phantom island that appeared on many maps of the period. To the northeast are Norway and the semi-mythical Bjarmaland, likely referring to the region around today’s Arkhangelsk in Russia.

At the top of the map we find Jötunheimar (“land of the giants”) and Risaland (“land of the titans”), mythological realms from Norse lore. Floating in the icy ocean is the fictional island of Narveöe. Two well-documented Greenlandic locations stand out: Hvitserkr, a glacier used by Icelandic sailors as a landmark, and Herjólfsnes, a settlement founded by one of the follower of Eiríkr the Red around 985.

A Greenland joined to America

One of the map’s most striking features is its depiction of Greenland as a peninsula connected to the North American continent. Clearly marked are saga toponyms: Helluland (“land of flat stones”), Markland (“land of forests”), Skrælingeland (“land of the natives”), and Promontorium Winlandiae—the Vinland promontory—placed at roughly the same latitude as Ireland’s southern coast, around 51°N.

This detail would prove crucial centuries later: in 1960, excavations at L’Anse-aux-Meadows, on the northern tip of Newfoundland, unearthed a Norse settlement from the 11th century—the first ever discovered in the New World. From obscure curiosity, the Skálholt Map suddenly became a valuable clue in historical research.

Not a mapmaking tradition, but a learned reconstruction

Contrary to what some have claimed, the Skálholt Map is not the remnant of an ancient Icelandic cartographic tradition. In fact, medieval Icelanders never developed a formal mapping practice. The map is instead the scholarly reconstruction of a 16th-century Icelandic intellectual, pieced together from literary texts, classical sources, and contemporary European maps.

Sigurður Stefánsson’s context was one of geopolitical maneuvering: Danish dominance over the North Atlantic—established by the Kalmar Union in 1397—was now driving the kingdom to seek historical legitimacy for territorial claims in the New World in the wake of Columbus’s voyages. Rediscovering the Norse sagas and their accounts of exploration served this colonial narrative well.

One striking episode was that of Danish archbishop Erik Valkendorf, who in 1519 secured papal permission to appoint a new bishop to Greenland—hoping to reestablish contact with Norse descendants after a century of silence following the plague. The voyage never materialized, but the navigational notes and accounts collected by Valkendorf, including those of Ivar Bárðarson, likely influenced Stefánsson’s mapmaking.

A map suspended between myth and politics

Despite its inaccuracies, the Skálholt Map is a document of tremendous historical significance. It reflects not only Iceland’s desire to keep alive the memory of its ancient explorers, but also Denmark’s political attempt to insert itself into the race for the Americas by asserting a kind of Norse “historical precedence” over post-Columbian colonial powers.

The map survives in manuscript copies (1669–1703), preserved in the Royal Danish Library and the Arnamagnæan Collection in Copenhagen. All feature the saga-derived names: Greenland, Helluland, Markland, Skrælingeland, and Promontorium Vinlandiae, in that order.

So while the Skálholt Map does not convey a medieval tradition of geographic knowledge passed down through the ages, it remains a brilliant example of Scandinavian erudition—an effort to reconstruct, from cultural memory and scattered texts, a past that Iceland was not ready to forget. A past of explorers, of remote churches buried in ice, and of settlers bold enough to sail across the ocean and touch the shores of America—centuries before Columbus ever left Palos.