Icelandic Music: the Langspil

The langspil is a traditional Icelandic musical instrument, whose name can be translated into English as “long instrument.” Its Icelandic pronunciation is [ˈlauŋkˌspɪːl̥], which can be approximated as “loung-spil” (the “ou” in first element is the same as in “bound” and the “g” is pronounced as a “k”) for those unfamiliar with the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Information on this instrument is remarkably scarce, as very little has been written about it. After a hiatus of several decades during the 20th century, the langspil is now experiencing a revival. This resurgence is linked to growing interest in traditional and ancient music, both in Iceland and abroad. Iceland, despite the small size of its population, boasts a very diverse music scene, with baroque ensembles alongside symphony orchestras and numerous choirs, some highly prestigious, reflecting a strong cultural tradition of musical participation.

The langspil belongs to the family of table zithers, more specifically to the subgroup known as drone zithers. While it likely descends from ancient Greek study instruments, its earliest direct ancestor is probably the German scheitholt, which is first mentioned in sources from the 14th century. Over time, this instrument inspired numerous regional variations across Alpine and northern European regions, leading to the development of many instruments modelled on the scheitholt.

Structure and Sound

The langspil consists of an elongated soundbox fitted with strings, typically one melodic string and one or more drone strings. The drone string provides a sustained note or chord, setting the harmonic foundation of a piece. A famous example of this concept can be found in the bagpipes, where drone pipes play a continuous tone alongside the melody. On a typical langspil, especially modern ones, the drone strings are tuned to the lower octave of the melodic string (e.g., a C if the melodic string is tuned to C) and the fifth (e.g., G, if the tuning is in C).

The instrument can be played either by plucking the strings, like a guitar, or with a bow, like a violin. It is held on the lap or placed on a flat surface. Modern commercial versions of the langspil allow players to perform a diatonic scale over two octaves, accommodating both the major and minor seventh. For instance, if tuned to C, it is possible to play both B♮ and B♭.

Historical References

The earliest known mentions of the langspil date back to the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1789, an English nobleman named John Thomas Stanley documented his travels in Iceland. In his journal, Stanley described a langspil he encountered on 28 August, noting its dimensions and form but remarking that “hardly any sound is as jarring to the ears as that produced by this instrument.”

Another reference appears in the biography of Jón Steingrímsson (1728–1791), known as the “Fire Priest.” Jón recounts how he was invited to play the langspil during a Christmas gathering and describes his mastery of the instrument, alongside singing. On another occasion, while visiting a home in Borgarfjörður, Jón observed a particularly beautiful langspil hanging on the wall. Though he initially declined to play due to lingering sorrow from the devastating 1783 eruption, the hostess performed soothing songs that lifted his spirits.

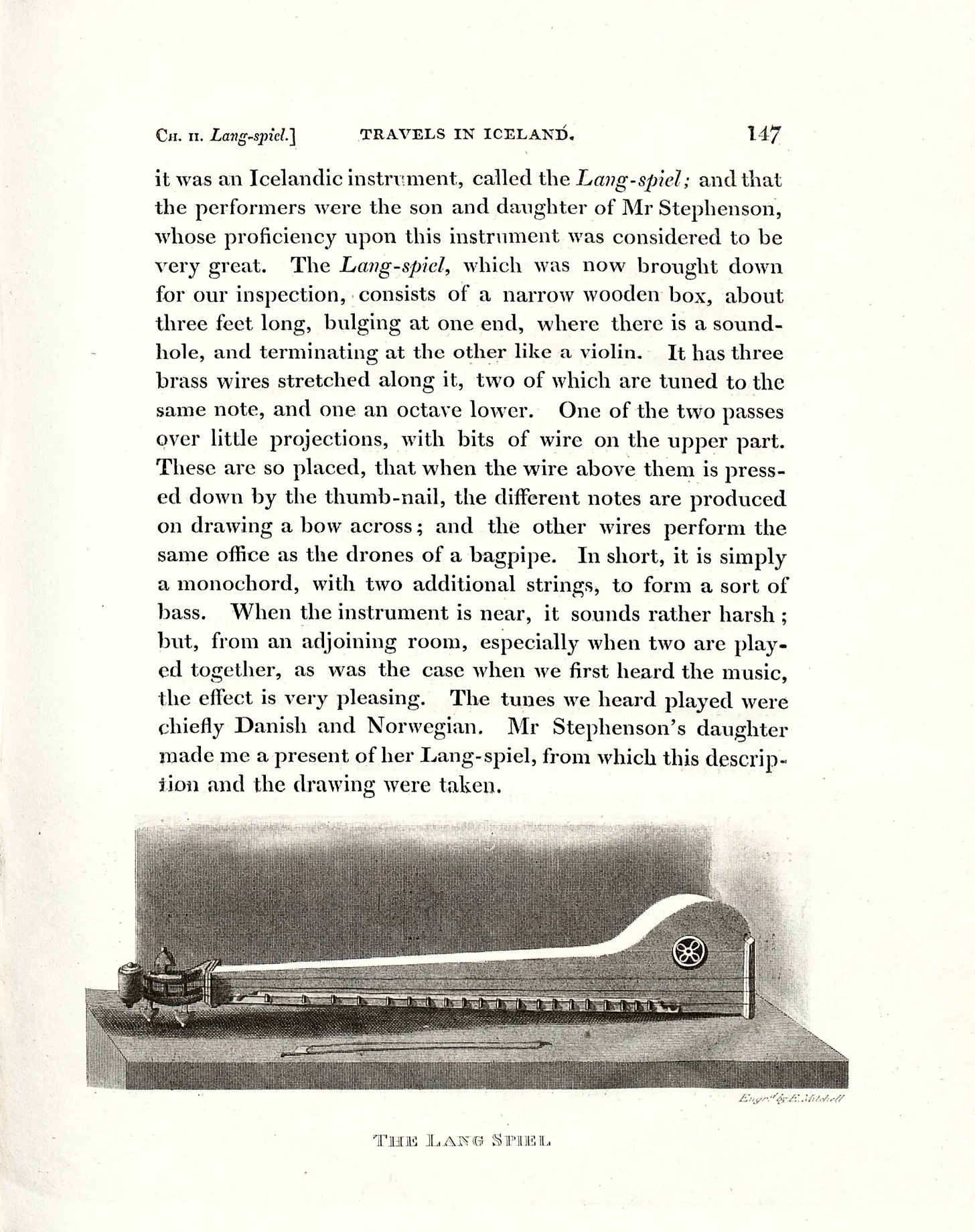

In 1811, Sir George Steuart Mackenzie, a British traveller, described hearing a langspil in vivid detail during his Icelandic journey. He recounted being pleasantly surprised by the instrument’s sound, mistaking it initially for piano music. Upon examination, Mackenzie described the langspil as a narrow wooden box with three brass strings—two tuned an octave apart and a third used for melody. While the instrument’s close-up sound was harsh, he found its effect pleasant when heard from an adjoining room, especially when played in harmony.

Construction and Evolution

Few ancient langspil instruments have been preserved, so knowledge of its early design and materials is limited. Traditionally, spruce—also used for violin soundboards—was the primary wood. Modern versions employ various woods, each contributing distinct acoustic properties. The langspil may be straight in shape (resembling a triangle) or curved (resembling a “b”), the latter being an innovation from the 19th century that improved sound quality. Resonance holes vary widely in shape, from circles and hearts to diamonds and floral patterns.

Historically, the langspil was played by pressing the melodic string with the left thumb to produce notes, while the other fingers remained slightly arched or glided along the soundbox. Both bowing and plucking techniques were employed, sometimes using a plectrum.

Notable Publications

The only known book on the langspil, Leiðarvísir til að spila á langspil og til að læra sálmalög eptir nótum (“A Guide to Playing the Langspil and Learning Hymns by Note”), was published in 1855 in Akureyri. This manual primarily aimed to teach the basics of music and provide accompaniment for Lutheran hymns. It reveals the limited musical knowledge of most Icelanders at the time and the challenges of preserving musical traditions without adequate resources. The author expressed regret over the difficulty of including musical notation due to printing costs.

Legacy

For much of its history, the langspil was Iceland’s primary instrument for accompanying sacred and secular music. It was only in the late 19th century that flutes and violins began to replace it. Today, the langspil is celebrated as a unique part of Icelandic heritage, offering a glimpse into the country’s musical past and its resilience in the face of cultural and material limitations.

Sources:

• Ari Sæmundsen, 1855, Leiðarvísir til að spila á langspil og til að læra sálmalög eptir nótum, Akureyri.

• Eyjólfur Eyjólfsson, 2020, Hughrif og handverk: Langspilið í upphafi 21. aldar, Reykjavík.

• Woods, David G., 1993, “Íslenska langspilið,” Árbók Hins íslenzka fornleifafélags.